Forgotten genocide in Flint?

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- | Last updated: Apr 4, 2017 - 11:57:27 AMWhat's your opinion on this article?

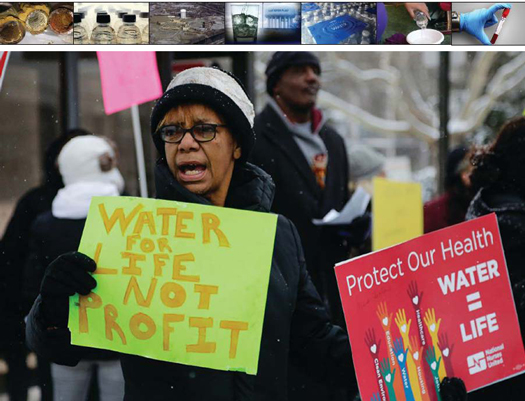

Flint resident Claire McClinton protests the quality of water with other concerned residents in front of Flint City Hall on Jan. 21, 2015 in downtown Flint, Mich. Flint is making headway in its efforts to fix its drinking water distribution and treatment systems, the state-appointed emergency manager said, as protesters derided the quality and cost of water in the city.

|

The suffering of a poor, majority Black city is far from over

“It’s like biological warfare.”

Those were the words of Yonasda Lonewolf, activist and author, on the eve of the “Water Is Life” expo in Flint, Michigan. The three-day event was organized by Ms. Lonewolf and other area activists to ensure that the water crisis in the majority Black city remains in the public eye and the national conversation.

Since 2014, Flint, with a population of a little more than 98,000—57 percent of whom are Black—has been without access to clean water, a situation that continues to this day. The poisoned water flowing into people’s homes has contributed to various health-related illnesses and in some cases, even death, for residents of a town where 41 percent live below the poverty line.

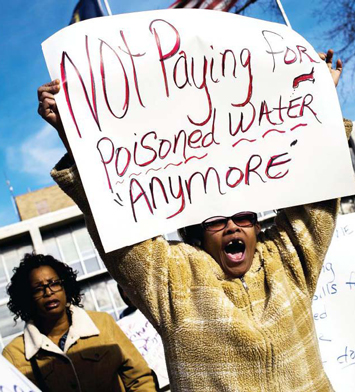

Flint resident Angela Hickmon, 56, chants during a protest outside City Hall in downtown Flint, Mich., Jan. 25, 2016. Michigan’s attorney general named a former prosecutor to spearhead an investigation into the process that left Flint’s drinking water tainted with lead, though Democrats questioned whether the special counsel would be impartial.

|

“From afar, I really didn’t know how bad the problems with the Flint water was. Probably like a lot of people, I thought that drinking bottled water should be an easy solution,” Ms. Lonewolf told The Final Call. “But when I heard that people were having skin problems and internal health issues, I realized that I wasn’t very educated about water.”

Ms. Lonewolf traveled to Flint and the gravity of the situation hit her when she tried to wash her hands in her hotel room.

“There was a sign that said not to use the water in the faucet, use the bottled water provided in the room to wash your hands. That’s when it hit me,” she said. “That’s when I realized that people in Flint have to use bottled water to wash their entire bodies. Every day, everything that you use faucet water for in your house, now you have to use bottled water? Immediately I felt like I had to do something.”

How did Flint happen?

Since 1967, the city had been purchasing its water from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department which is sourced directly from Lake Huron. However, in 2014, construction on a new pipeline began that would allow Flint to source its water from Lake Huron, eliminating the need to pay the city of Detroit. In the interim, the city’s water source was switched over to the Flint River until the pipeline was completed.

However, this was all done without the residents of Flint having any say in the matter because locally, it was well known that the river’s water was toxic. And according to a July 2001 assessment of the Flint River conducted by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, the condition of the water was known at the highest level of state government.

The report concluded that upstream, water quality in the river was fair to good. Downstream, where the city of Flint is located, unregulated industrial discharges into the water—such as industrial waste from the General Motors auto factory—had severely degraded the water to the point where it contained high levels of “fecal coliform bacteria, low dissolved oxygen, plant nutrients, oils and toxic substances.”

Compounding the problem was the city’s lead water lines which were already old and corroding. Sourcing the contaminated water from the Flint River accelerated the lead pipe corrosion, while at the same time, introduced bacteria from the river into the system which then flowed into people’s homes and ultimately, poisoning them.

Flint was virtually locked out of the decision regarding the water sourcing switch because of law signed by Michigan’s Republican governor Rick Snyder, during a 2012 lame duck state legislature session—a law that incidentally, is shielded from challenge via referendum.

(L) Flint resident Brittani Felton shows pictures taken on Jan. 30 of rashes she said occurred from showering in the water in her living room as Waldorf & Sons Excavating digs up and changes the first lead service line in Flint on March 3, 2016, Flint, Mich. Photo: Jake May/The Flint Journal-MLive.com via AP (R) In this April 5, 2016 photo, Darlene Long points to photos of swollen fingers and hair loss on her daughter to show Attorney Paul Novak before Flint Water Class Action Team's community meeting for Flint residents at Dort Federal Credit Union Event Center in Flint, Mich. Photo: Rachel Woolf/The Flint Journal-MLive.com via AP

|

Public Act 436 gives the state the authority through an appointed individual to essentially take over any local government or school district found to be in a state of financial emergency—like the city of Flint, which was found to be operating at a $25 million deficit after a 2011 Michigan Department of Treasury audit.

This person has authority to set ordinances, terminate, modify and even reject labor agreements, as well as sell off any assets—such as water—held by the school district or local government it assumes control over.

“This is when our problems really began,” said Claire McClinton, a Flint resident who has been one of the more outspoken voices raising awareness to the city’s water crisis. “We have had 17 emergency managers dispatched around the state to take over primarily African-American cities and school districts that have financial issues. These individuals have total dictatorial powers and when they come in, they set aside your local government—your city council or your mayor no longer has any power. They are irrelevant. This is the untold story of Flint. Our water was switched by an emergency manager who pulled the trigger and poisoned this city. It’s like a dictatorship going on here in Michigan. Privatizing services and selling off assets is the main purpose of the emergency manager.

“If they would’ve asked the citizens of Flint if we wanted to get our water from the Flint River, we wouldn’t have to be environmental scientists or experts to know that the river water—with all the years of industrial waste being pumped into the water from car manufacturing and everything else that contaminated it—was bad. We would’ve said no to that because we didn’t trust that water.”

The aftermath of the switch

Two months after water from the Flint River began flowing through the system, residents began reporting brown, foul smelling water coming out of the water faucets and shower heads in their homes. Many complained of skin rashes, hair loss, and multiple deaths occurred from Legionnaires Disease.

(L) Flint city River, Michigan (R) Discolored Flint water samples, next to relatively clear samples from the same lot. Photo: Flint water study/Facebook

|

“My mom is a senior and she had a huge rash on her entire back. My daughter got sick; she started developing huge bumps on her body and carrying a fever. My granddaughter started getting nosebleeds, and my hair started falling out,” said April Cook-Hawkins, one of the local organizers of the Flint water expo, who is also first lady of Prince of Peace Baptist Church, pastored by her husband, Rev. Jeffrey Hawkins Sr.

“Just recently, my five-day-old granddaughter passed,” Mrs. Hawkins said. “My son and his girlfriend never made it out of the hospital with their baby because she contracted some bacteria that the doctors didn’t recognize. She had to be quarantined and that’s when she passed away. We think it was water-related too.”

Once word of the situation got out, a Virginia Tech Research Team, led by professor Marc Edwards, came to Flint to test the water. It was discovered that federal law was being violated by the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality who wasn’t treating the Flint River with a required anti-corrosive agent. This made the water in Flint 19 times more corrosive than the water in Detroit and explains the presence of such high amounts of lead in the water—levels that Prof. Edwards says he hadn’t seen anywhere in the country in more than 25 years. He found that a glass of Flint water could raise the level of lead in a child’s blood eight times above the lead poisoning threshold.

“Six months after the water switch, General Motors told the city they couldn’t use the Flint water because it was rusting the engine parts they were building,” Ms. McClinton said. “The emergency manager authorized General Motors to go back to using the Detroit water system, but wouldn’t authorize to switch Flint back over because they said it would be too expensive.”

Two months later, in June 2015, a lawsuit was filed against the city, citing the use of Flint River water as a health risk to the people. In September of the same year, the case was dismissed, even though it was discovered that same month that 40 percent of homes in Flint had elevated levels of lead in the water.

Yonasda Lonewolf, who is of Native American and Black descent, is all too familiar with the effects of environmental poisoning while being on the front lines at Standing Rock protesting the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline.

“We were at war in Standing Rock. I felt that it was my duty as a human to help protect all of the animals and people who got water from the Missouri River, from the oil pipelines because we know that they can leak and contaminate the river,” she explained. “That land is treaty land. It belongs to indigenous people, not America. While we were there protesting, we were all dealing with something called DAPL (Dakota Access Pipeline) cough because they were spraying us with water, plus there was always teargas smoke in the air. I went to the doctor and they told me it was a different strain of strep throat that they’d never seen and since Standing Rock, my immune system is much weaker than it was before. They can really attack you and kill you through the water.”

For almost three years, untold gallons of water have been donated to the City of Flint as its residents patiently waited for a resolution to the water problem. One temporary solution was the use of filters. One of the goals of the Water is Life expo was to educate those in attendance on the best available whole house filters, as well as those that can be installed on a faucet or even shower head. The state of Michigan has provided Flint residents with filters and replacement cartridges for the next three years.

However, Ms. McClinton says of the filters, “they may filter out the lead, but they’re not equipped to filter out the bacteria that’s still in the water.”

Strangely, the situation has not been declared a federal disaster, another point of contention and anger among Flint residents. Barack Obama declined to declare the area a disaster when he was president, instead electing to authorize $5 million in aid to the city.

“When an area is classified as a disaster area, there are super funds and other resources available to be used to help the people affected,” Ms. McClinton explained. “FEMA and the Army Corps of Engineers could come in and help dig up the pipes in Flint and work to replace them.”

Ironically, the pipeline connecting Flint directly to Lake Huron has been completed. All of the municipalities of Genesee County have been switched over, except for the City of Flint because the pipes are already irreparably corroded.

“You could pump the freshest water ever created into Flint,” Ms. McClinton explained. “But because the pipes are already so corroded, it wouldn’t do any good.”

“The impacts of lead, especially to young children and those moving into their teenage years, follow you for the rest of your life,” Mustafa Ali, former head of the environmental justice program at the EPA, told The Final Call. “The challenges that lead poisoning presents are just devastating because they play out in so many different ways, especially in the neurological aspect. Children can have challenges with learning, which leads to challenges in school, and this sets you up for another set of choices you have to make when you can’t find a job. Then you end up in the system and we all know what the outcome is once that happens.”

Since 2014, lawsuits and criminal charges have been filed, congressional hearings have been held and in February 2017, the Michigan Civil Rights Commission released a 129-page report titled, “The Flint Water Crisis: Systemic Racism Through the Lens of Flint.” This study found historical, institutional and systemic racism played a major role in the decision to source the city’s water through the Flint River. In March, the Environmental Protection Agency announced a $100 million grant to Flint to upgrade its water infrastructure, and on March 28, 2017, a U.S. district judge in Detroit approved that those funds be used to remove both lead-lined and galvanized steel pipes that deliver water to 18,000 residences in Flint.

The state will be required to spend $87 million to inspect, remove and replace the water lines in the city, with the remaining balance being set aside for any other additional expenses. In addition, both the city of Flint and the state of Michigan will be required to pay $1 million to plaintiffs who have filed water-related lawsuits.

Moving forward and looking ahead

Flint is one of many predominantly Black cities currently dealing with environmental issues. The Calumet neighborhood in East Chicago, Indiana, is dealing with high levels of lead and arsenic in the soil around homes. Baltimore, Newark, Cleveland, and as many as 3,000 other locations in America, are dealing with elevated lead levels in water. However, with the election of Donald Trump, his administration has aimed at deregulation and cutting budgets of agencies like the EPA, hampering their ability to adequately address these issues.

A Michigan National Guard member provides water to a resident of Flint, which is enduring a drinking water crisis due to lead contamination of the city's water source. Photo: Michigan National Guard

|

This is one of the primary reasons Mustafa Ali resigned from EPA after 24 years with the agency. Since leaving EPA, Mr. Ali has joined on with the Hip Hop Caucus to continue his fight for environmental justice for communities of color, which are disproportionately affected by environmental issues.

“African-American, and other communities of color, are located the closest to coal-fired power plants, incinerators, chemical facilities, landfills; all these various things are in, or close to our communities,” Mr. Ali said. “We’re impacted negatively by these businesses and industries in terms of environmental pollution, as well by the traffic that’s moving through our communities.

“For example, if there’s a landfill in a community, you have to be careful of the lining that’s in place, otherwise you’ll have toxins leaching in the ground water. But you also have the garbage trucks that are bringing waste into these spaces contaminating the air, not to mention the fact that major transportation routes often run right through or are adjacent communities.

“So, there’s two sides to this coin. You have the environmental injustice, which are the negative impacts that we’re discussing, and there’s environmental justice of where we’re trying to help communities move to where they are equitable and sustainable for the people who live there. Most times, people won’t discuss the justice side of the coin. Mostly you’ll hear people fighting just to stop the pollution affecting their communities.”

Mr. Ali says unity around these issues can help drive change and people aren’t at the mercy of the federal, state or even local government to correct these problems. But first, people must educate themselves on these issues and begin to train to become part of the solution.

“If we do this work right, and get in front of it, we can make sure that communities that are often unheard or overlooked, can get the help they need to move into a better place,” he said. “We can really begin to change the dynamics that are going on. But if we don’t, it’s just going to push us further down.”

There are a number of grassroots, green and even STEM organizations that are looking ahead to the future and working to help people to protect themselves from environmental issues plaguing their communities.

|

“People have power. And whether I’m talking to somebody in the White House or the barbershop, I tell them that because they are taxpayers, people have a right to demand that their tax dollars are utilized in ways that are going to be helpful to their communities,” Mr. Ali said. “I know we’re all busy and many of us are just trying to survive, but we have to come together and stop being focused on surviving and begin to learn how to thrive. We have to carve out a little bit of time to make sure that people at every level of government are hearing your voices and that you will hold them accountable. You have power in that situation.”

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!