Mass Incarceration And The Failure Of Black School Children

By Nisa Islam Muhammad -Staff Writer- | Last updated: Mar 22, 2017 - 10:01:36 AMWhat's your opinion on this article?

|

WASHINGTON—When “Debra,” not her real name, left to do a mandatory four-year minimum sentence for drug possession, she left her five-year-old daughter with her mother. It was her only option for care. Debra’s mom would be responsible for everything. Debra could only pray for a good outcome.

“I was heartsick at having to leave her but I had to go. I just hoped for the best and did all I could to stay in contact with both of them. I knew my mom barely had a high school education so homework was going to be an issue but it was just elementary school so I wasn’t that concerned,” Debra told The Final Call.

“But then my mom got sick and there were days when my daughter missed school, homework wasn’t getting done and now she was in the third grade. She missed so much school that she had to repeat the third grade and that just caused more problems. Her friends teased her, she was bullied and then didn’t want to go to school. I cried a river of tears because there was no one to help me with my daughter.”

For the first time mass incarceration and racial achievement gaps were connected directly in a new study by the Economic Policy Institute released at a March 15 media event.

EPI research associates Leila Morsy and Richard Rothstein found overwhelming evidence that having an incarcerated parent leads to an array of negative outcomes that affect a child’s school performance.

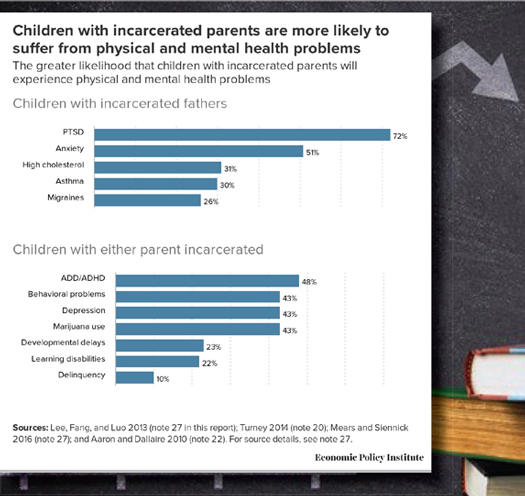

Independent of other social and economic characteristics, children of incarcerated parents are more likely to misbehave in school, drop out of school, develop learning disabilities, experience homelessness, or suffer from conditions such as migraines, asthma, high cholesterol, depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

|

“Simply put, criminal justice policy is education policy,” said Ms. Morsy. “It is impossible to disentangle the racial achievement gap from the extraordinary rise in incarceration in the United States. Education policymakers, educators, and advocates should pay greater attention to the mass incarceration of young African Americans.”

Black children are six times as likely as White children to have a parent who is or has been incarcerated. One in four Black students have a parent who is or has been incarcerated, and as many as one in 10 have a parent who is currently incarcerated. Because Black children are disproportionately likely to have had an incarcerated parent, the authors argue, the United States history of mass incarceration has contributed significantly to gaps in achievement between Black and White students.

“Despite increased national interest in criminal justice reform, President Trump has promised to move in the opposite direction by advocating for a nationwide ‘stop-and-frisk’ program,” said Mr. Rothstein. “While the chance of reform on a federal level may have stalled, advocates should look for opportunities for reform at the state and local levels, because many more parents are incarcerated in state than in federal prisons.”

The report found a Black child is six times as likely as a White child to have or have had an incarcerated parent. A growing number of Blacks have been arrested for drug crimes, yet Blacks are no more likely than Whites to sell or use drugs.

At the inner city school in Washington, D.C., where Nasser Muhammad teaches third through fifth grade special education, he suspects many of his students may have had an incarcerated parent at one point.

“If it’s the father that’s incarcerated, the sons don’t have someone to look up to as they are growing up. They don’t have the balance they need to grow up successfully. Boys imitate strength and power. If dad is gone they imitate the strength and power of mom. We see the aftereffects in the classroom,” he told The Final Call.

“Girls need their fathers also to teach them how they are supposed to be respected as young ladies. When dad is incarcerated, many think it doesn’t affect girls but it does and we see it in the classroom too.”

Ms. Morsy explained how the problem of an incarcerated parent is more severe and complicated than people have understood.

“When someone is incarcerated it means a loss of income in that family, even when released they can be formally or informally barred from employment. This loss leads a family to a range of problems: Increase in housing instability, more moving around, increase in exposure to violence, higher likelihood of instability in parents’ relationships.”

The authors advocate for policies that counter these problems by reducing incarceration, including eliminating disparities between minimum sentences for possession of crack versus powder cocaine, repealing mandatory minimum sentences for minor drug offenses and other nonviolent crimes, and increasing funding for social, educational, and employment programs for released offenders.

Glenn Loury, Merton P. Stoltz professor of the Social Sciences at Brown University, sent a written statement to the press event because his flight was cancelled due to bad weather. He’s not convinced by the report. Mr. Loury questioned whether the same behavior that got a parent arrested would be sufficient to help their children be academically successful in school.

But the report authors disagreed. They contend, “This growth in the share of African-American children suffering from parental incarceration has in all probability offset many efforts to raise the average achievement levels of these children during the last 35 years.”

“Although the share of White children with a father in prison has grown comparably (from 0.5 percent to 2 percent), the concentration in low-income neighborhoods of African-American children with imprisoned fathers presents challenges to teachers and schools unlike those presented by the relatively rare White child with an imprisoned father.”

The report concluded, “The problem of mass incarceration for drug crimes, however, is not typically thought of as an educational crisis, and it is an issue that educational policymakers have little experience in confronting. How educators can add their voices to demands for an end to this war is a challenge that we should all begin to confront, if our other educational reform efforts are not to be frustrated by unjustifiable criminal justice policy and practice.”

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!