The legacy of Dr. Matilda Evans: A history of service

By Brian E. Muhammad -Contributing Writer- | Last updated: Jun 5, 2019 - 12:19:44 PMWhat's your opinion on this article?

“History, of all our studies, is most attractive and best qualified to reward our research, as it develops the springs and motives of human actions and displays the consequences of circumstances which operate most powerfully on the destinies of human beings.” –The Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad (1936)

Dr. Matilda Evans in operating room.

|

Several organizations that preserve sites and narratives of Black South Carolina held ceremonies late March celebrating Dr. Evans’ contributions to health care and Black achievement.

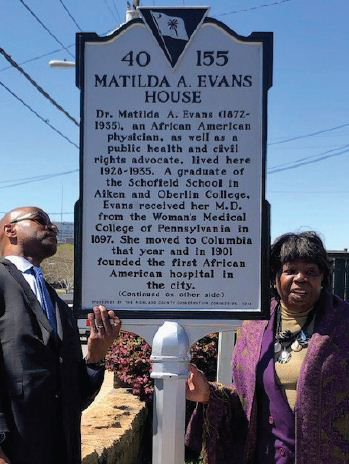

The Richland County Conservation Commission dedicated a historical marker at her home near downtown Columbia, placing it on the National Register of Historic Places. On the same day, the Good Samaritan-Waverly Hospital—now owned by the historically Black Allen University—was marked as well. Both are significant sites to the Black experience in South Carolina.

“These are two sites that were fashioned and shaped during the turn of the 20th Century, when most rights for African-Americans were deprived; when resources were denied,” said Dr. Bobby Donaldson, director of the Center for Civil Rights History and Research at the University of South Carolina.

He explained both sites represent examples where Blacks “determined to build a nation on their own” and created institutions like churches, schools, and hospitals for Blacks during the height of segregation.

“Dr. Evans was a pioneer in that effort,” Dr. Donaldson told The Final Call.

Dr. Burnie Gallman, who was a physician at Good Samaritan-Waverly Hospital, added, the recognition is key for the current generation.

“African people in America have lost our history. In many cases it’s been taken away from us. But the problem … even more pervasive … is that we’ve lost our taste to learn our history,” said Dr. Gallman.

History exposes past accomplishment, so “we don’t have to recreate” the wheel. “All we have to do is respect and study our ancestors and build upon what they did,” Dr. Gallman added.

Dr. Evans is an unsung woman whose magnitude of service made her a trailblazer in the field of medicine and medical training. She pursued medicine at the encouragement of Martha Schofield, a Quaker educator who through her Schofield Normal and Industrial School in Aiken, S.C., mentored young Matilda.

Dr. Evans was born June 23, 1872, in Aiken and was a Schofield graduate who attended Oberlin College in Ohio on scholarship and the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, where she received her M.D. in 1897.

Historical marker in front of home of Dr. Evans.

|

She practiced Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Surgery. In 1901, she established Taylor Lane Hospital, the first Black hospital in Columbia, S.C. When the hospital was destroyed by fire, she started St. Luke’s Hospital and School of Nursing. She founded the Good Health Association of South Carolina to educate people about preventive health practices and safe, sanitary habits. She provided a free clinic for Black children needing medical treatment and vaccinations.

Uplifting the legacy of Dr. Evans comes at a critical time in the 21st Century. The numbers of Black physicians in South Carolina are dismally low and Black statewide statistics for chronic illnesses are relatively high. The U.S. Census says nationally Blacks make up 13.4 percent of the population. In South Carolina, Blacks are 27.3 percent, but only a meager six percent of physicians.

According to 2017 figures of the South Carolina Office for Healthcare Workforce, of all 12,741 doctors practicing in South Carolina, 783 were Black.

“It’s important to know her history because her history is a history of service, especially to her people,” said Beverly Muhammad of Atlanta and a granddaughter of Dr. Evans. “She did not deny patients,” she said. “She had Caucasian patients too, because she was the doctor.”

Dr. Evans did this during some of the worst years of racial oppression and White domestic terrorism against Blacks. Some Whites went to Dr. Evans “because they were too poor, and she would always find a way to help people,” said Ms. Muhammad, recalling accounts shared by her own mother, Mattie Aikens.

Dr. Evans’ commitment of serving others was influenced by the example she witnessed of the Quakers and Ms. Schofield who came to South Carolina from Pennsylvania as missionaries and abolitionists. Ms. Schofield saw the intellect of Matilda as a child and facilitated her advanced education.

“Dr. Evans was a strong minded, strong willed woman who lived with unselfish purpose to educate and to uplift her people,” recounted Ms. Muhammad.

“Many times, she was militant, but many times she penned her militancy under the name of the Quaker woman Martha Schofield, because in that day and time she couldn’t speak forthrightly about what she believed in because it would get her killed,” she said.

Referencing papers and writings by her grandmother, Ms. Muhammad described the profundity of Dr. Evans’ thinking and vision concerning justice and the American race dilemma.

“Dr. Evans proposed adoption of separation of the Negroes from the Whites in a land that she felt Whites should give the Negro for enslaving them against their will and she proposed that these states … should be called Negro land,” Ms. Muhammad told The Final Call.

“Dr. Evans believed strongly that the Negro is ready for self-government and that is proved by the efficiency of the Negro recorded after the Civil War to do for self,” she said

Ms. Muhammad also recalled her mother Mattie sharing Dr. Evans’ lesson that there are “some Whites that are willing to help the ‘Negro’ due to the fact that a fear what the Negro will do, once they wake up.”

She noted that these views were “planted over a hundred years ago” by Dr. Evans and is being published publicly for the first time in The Final Call. Her grandmother’s thoughts and actions were on time and before time. “They’re more relevant today,” added Ms. Muhammad.

Dr. Matilda Evans’ home

|

Ms. Muhammad is the oldest of Dr. Evans’ four grandchildren and with her husband Student FOI Captain Tim Muhammad is a longtime member of the Nation of Islam pushing to preserve Dr. Evans’ legacy.

Although Ms. Muhammad admits, among scholars who study Dr. Evans, the views aren’t popular, she doesn’t believe her grandmother came upon these thoughts on her own.

She said perhaps Dr. Evans met Master Fard Muhammad, founder of the Nation of Islam, in his travels during the early 1900s. Dr. Evans’ writings about separation and justice correlates to the teachings of the 89-year-old Nation of Islam movement.

Ms. Muhammad said God has “preserved the best part” of Dr. Evans’ writings to “settle upon the thought of our people” and bears witness to solutions for the problem of Black life advanced currently by the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan.

Dr. Matilda Evans passed away in 1935, but she lives in the saga of her contribution, and the profound vision she expressed for her people.

As Dr. Evans placed her mark on South Carolina, her legacy expands beyond. “The true inheritance of Dr. Evans belongs to the Nation of Islam,” said Ms. Muhammad.

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!