Hope, history and Harriet: Divided opinions about movie depiction of a Black heroine

By by Richard B. Muhammad and Bryan 18X Crawford The Final Call @TheFinalCall | Last updated: Nov 20, 2019 - 10:35:54 AMWhat's your opinion on this article?

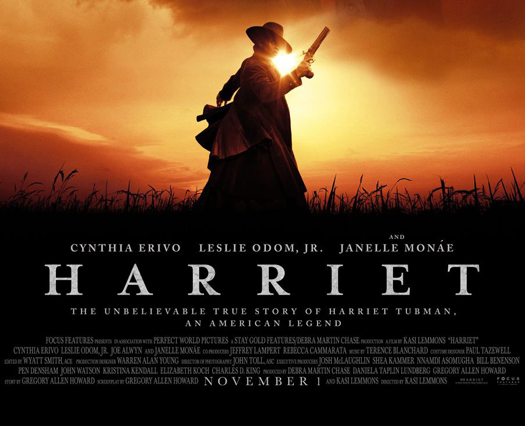

A film celebrating an iconic Black abolitionist and freedom fighter has emerged as a subject for often heated debate about depiction of the life and times of Harriet Tubman.

Critics often point to problems with what they as historical accuracies—and a sly use of the slave master as a hero. Others say they are tired of slave movies, while another view rejects a film about the Black American experience that fails to use a Black American in the title role.

Defenders of the film see a Black heroine portrayed almost as a superhero. And, they add, many of the detractors never saw the movie, which faced an organized boycott.

There is clearly a political dimension as many in the self-proclaimed ADOS (American Descendants of Slaves) group complained about using a woman who is not a Black American in the title role. That criticism is part of the ADOS insistence that Black Americans are their own separate group and should not be linked to any Pan African sentiments. Their view is Blacks in America should stand alone as a separate and distinct tribe when it comes to reparations, racial progress and opportunity. There was a concerted effort by the group to organize against the movie.

Lastly, the movie’s strong representation of Harriet’s faith and connection with God shines through and many found that connection inspiring.

In an interview with IndieWire, “Harriet” writer and director Kasi Lemmons, admitted to embellishing and making up portions of the film.

“Of course I embellished, I’m a screenwriter,” Ms. Lemons, who co-wrote the script with Gregory Allen Howard, a Black man, told IndieWire. “I added to the story because anybody that’s a writer that approaches a real story has to embellish.”

The Black filmmaker, who drew praise for her 1997 movie Eve’s Bayou, took on the task and many expressed appreciation for her work.

In the movie, Harriet doesn’t cower or grovel and literally prays for the death of her slavemaster. When caught running away from her owner’s Maryland plantation, she jumps to almost certain death into a river. It’s freedom or death, she declares.

Once she arrives in Philadelphia, she connects with the Underground Railroad and despite insistence that she not return, Harriet heads back South and rescues family members and other slaves.

The movie captures some of the insecurity that came with passage of the federal Fugitive Slave Act in 1850. Prior to the act, Blacks could enjoy a measure of security if they made it North. But once the act passed, as a result of anger over runaway slaves, federal marshals become part of the slave catching army and others made their way North determined to retrieve their property or earn rewards by dragging slaves back to their master. Kidnappers snatched free Blacks and sold them into slavery.

Though her family flees to Canada, Harriett returns again to liberate more of her captive brethren, despite the new law.

There are no White saviours in this movie as Harriet rejects admonitions from others that she stop acting as a Moses for her people.

The movie gives an indication of the value of slaves in a scene where Harriet’s former mistress is distraught about the loss of fleeing slaves, saying the runaways alone were worth nearly half the price of her farm. She also balks, but later relents, at selling slaves saying her position in the community is tied to the number of slaves she owns.

The film closes with Harriet leading colored troops into battle during the Civil War as a crowd of slaves rush forward, their White masters at their heels. Harriet and the Black soldiers raise their weapons, firing shots to take their own freedom.

Several characters in the film, including Philadelphia free Black woman Marie Buchanan, played by singer Janelle Monae; Walter, a onetime Black slave catcher who becomes a Harriet ally; and Gideon, the slave owner, were all fictionalized.

Two of the loudest complaints related to “Bigger Long,” a brutal fictionalized Black slavecatcher, and what critics claim is a “White savior” theme when slavemaster Gideon kills negro Long as they seek to capture Harriet.

“There’s a difference between taking liberties with a script, and making up a complete fictional narrative altogether,” independent filmmaker Tariq Nasheed, creator of the “Hidden Colors” documentary series and “1804: The Hidden History of Haiti,” told The Final Call. “They made up a character who was actually the bad guy in the movie, Bigger Long. That’s a horrible name that has sexual connotations to it. This character was the most violent and the most brutal in the film, and the Harriet character had to be saved from this big, bad Black man, by the White slave owner. So, they crowbarred in a White savior narrative in this film. This, to me, is science fiction. It’s not even regular fiction.”

That’s one view.

In the movie, however, Whites make it clear they want Harriet alive and Gideon, after killing the race traitor, declares he ordered the negro to take her alive. Confronted by the slavemaster, Harriet shoots him in the hand, possibly crippling him. She prophesies to him about a bloody war over slavery that is coming and tells him God never intended for people to own people. She takes his horse and rides away, leaving her humiliated former master holding a bloody stump of a hand and sitting on the ground.

As of Nov. 15, the movie had grossed about $26.5 million in sales and cost $17 million to make.

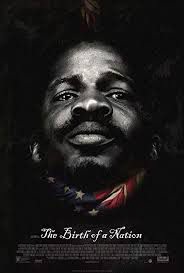

Nate Parker’s “The Birth of a Nation” based on the life of Nat Turner made roughly $17 million at the box office, doubling the $8.5 million it took to make it.

The movie “12 Years a Slave,” based on the true story of a free Black man from New York who spent more than a decade as a slave in Louisiana, made $188 million at the box office against a $22 million budget. “Django,” the fictionalized Quentin Tarantino movie made $425 million at the box office, costing only $100 million to make.

Fact vs. Fiction vs. Entertainment

Both “The Birth of a Nation” and “Harriet” were discussed as potential Oscar-winners prior to their release. Polarized conversations hit Black social media before both films came out. Some critics feel that unlike Ms. Lemmons’ film, Mr. Parker tried to remain authentic to the life of the real person portrayed on film.

“ ‘The Birth of a Nation’ was a lot closer to the real life of Nat Turner, and it gave a much truer picture of what his rebellion was all about. You can put other stuff in a movie, but as long as it has the same spirit, the additional fictional storylines can enhance the spirit of the project,” argued Mr. Nasheed, who has been aligned with ADOS at times. “But embellishment can turn into disrespect when you start going crazy with the liberalization of stories about real people. And with Black movies that seems to be okay. But put a Black actor in the place of where a fictional comic book superhero is supposed to be, and White folks lose their minds. So, they don’t let you mess around with none of their narratives—even if they’re fictional—but they divide and flip up our films as they see fit.”

Mr. Nasheed believes the more money Hollywood pumps into a movie about slave era films, the further away you get from a true, authentic telling of the story. Another problem is reliance on movies to teach historical facts.

Others saw Harriet as a pistol packing “bad ass,” fearless, and determined to free her people. “OMG! I came out of harrietfilm feeling like a BOSS! @cynthiaerivo KILLED this role and made me feel the strength and the vulnerability of #HarrietTubman So proud of you sis!” said Naturi Naughton on Twitter. The actress and singer is featured on the Starz hit show “Power.”

“#HarrietMovie was good, yall critics are high,” @Treasure__C, who described herself as a believer, activist and listener, said on Twitter. “So glad I went to go see it, cause I started to boycott because of yall. If only some of us had the drive that #HarrietTubman had,” she added.

“Until I have seen the film, I cannot criticize it. But I hope everyone who is criticizing it is basing their thoughts on what they have seen and researched, not what they have heard,” Rochelle Riley, a onetime journalist and director of arts and culture for the city of Detroit, told The Final Call. “I do know that [‘Harriet’] is not a documentary, but a feature film, and I will go into the theater knowing that.”

“When watching the movie, I was blown away. It was an awesome depiction of Harriet [Tubman],” Twitter user “Shae The Writer” told The Final Call. “This movie painted Harriet [Tubman] as strong, courageous Black woman who let God’s voice lead herself—and many others—to freedom. The main thing I took from this movie was to face your fears, trust God no matter what, and never believe anyone who tells you what you can’t do.”

Many supporters of the film celebrate it for simply being a Hollywood-produced adaptation of the life of a real Black freedom fighter and abolitionist. Just the simple fact of a movie like this being presented to the masses could plant the seed that sets a young Black mind on the path to learning more about the lives of those who fought for freedom and against oppression.

These same supporters also say that it is inspiring to see the life of a strong, Black woman portrayed on the big screen; one that truly gives the viewer a glimpse into the mindset of Black people during one of the most horrific times in their sojourn in North America.

“I saw ‘Harriet’ and I thought of the Black woman, and I thought of the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan in [the context of] her loyalty to Black people, and her refusal to leave us behind,” Nation of Islam Minister Ava Muhammad, national spokesperson for Min. Farrakhan, said on a recent episode of her “Elevated Places” online radio show.

“[Harriet Tubman] could have lived a life of comfort and ease, and she refused to do that. She refused to abandon her people,” Dr. Muhammad added. “Everything she did was in response to the direct guidance from Allah; from God. When she prayed, she prayed with her hands outstretched, palms up, like we pray in Islam … Throughout this film, you saw one scene after another that confirm, yet again, the teachings of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, and confirm that when we are our natural, normal selves, we want nothing to do with these people. We want to get as far away from them as possible. And it was not until integration that we became truly other than ourselves.”

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!