The Berlin Conference and the conquest, rape of Africa

By Jehron Muhammad | Last updated: Dec 4, 2019 - 11:53:48 AMWhat's your opinion on this article?

|

“Diplomatic in form, it was economic in fact; ostensibly international in its bearings,” noted the 1886 Political Science Quarterly (PSQ), in a review of “The Conference at Berlin on the West-African Question.”

Some years ago to explain to students how Africa was divvied up in 1884-85 by European powers, I stood in front of my son’s sixth grade class armed only with a magic marker. I drew as Europeans once did “artificial borders” on a map of Africa, then devoid of its current nation states, that was projected from the Internet onto an erasable board.

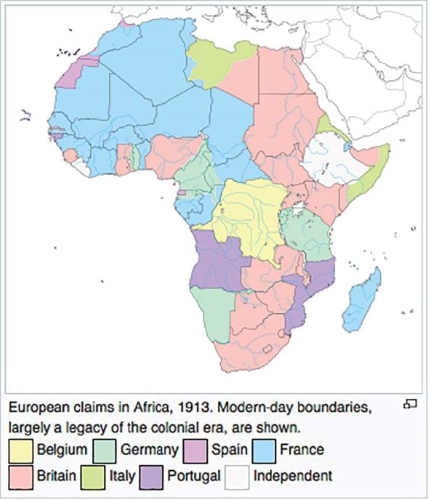

According to the documentary “Scramble for Africa,” the 1885 Act of Berlin did the same thing, carve up Africa by simply drawing lines on a map. “Places where they had not even been yet. Between 6,000 and 10,000 political units were carved up.” “People … were just cut off from (water sources) … it was complete geographical madness,” recounted the documentary.

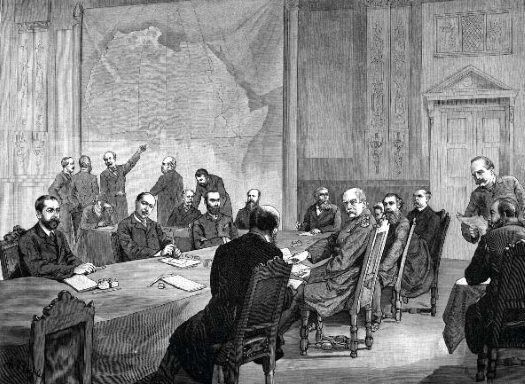

The conference of Berlin, as illustrated in “Illustrierte Zeitung.”

|

Acquainting 11 and 12 year olds with a system of exploitation that has spanned the globe was truly a daunting task. But teaching the history of European land acquisition by might of arms is the principal missing ingredient in Western education and deserves much discussion, research and reflection.

Nairobi communications consultant and political cartoonist Patrick Gathara—and the 1886 Political Science Quarterly bears him out—argued the perception of “delegates … hunched over a map, armed with rulers and pencils, sketching out national borders on the continent, with no idea of what existed on the ground” is a false one. In fact, according to the PSQ, by the time of the Berlin Conference the division of Africa had been well underway.

Gathara, who appeared in a recent edition of Al Jazeera, states that the conference was also not designed to partition the continent. The conference, says Gathara, did something far worse. With “consequences that would reverberate across the years and be felt until today, it established the rules for the conquest and partition of Africa, in the process legitimizing the ideas of Africa as a playground for outsiders, its mineral wealth as a resource for the outside world not for Africans and its fate as a matter not to be left to Africans,” he said.

This template and others have withstood the test of time. Other iterations of the Berlin conference include the Rome Treaty of 1957. “In Rome, six European countries, without involvement of any Africans, promised each other equal access to trading and investment opportunities in what is today the territory of 21 African countries: Senegal, Mali, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Benin, Mauritania, Niger, Burkina Faso, the Republic of the Congo (Congo Brazzaville), the Central African Republic, Chad, Gabon, the Comoros, Madagascar, Djibouti, Togo, Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) Rwanda, Burundi and Somalia.

“In fact,” according to Gathara, “as noted by Hansen and Jonsson, three-quarters of the territory covered by the EEC actually lay outside continental Europe, the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community.”

Other forms of continued African economic and land exploitation can be seen in Southern Africa.

According to a “Review of Land Reforms In Southern Africa,” “The countries of southern Africa share similar histories of colonization and dispossession, histories that continue to shape current patterns of land tenure and administration. Most of the countries in the region have been through a phase of liberalization and market reforms, or market-related land redistribution programs, and since the 1990s new land laws have been passed in several countries, which tend to have been relatively weakly implemented and enforced.”

|

South Africa is a case in point. Coming out of prison, many called Nelson Mandela a nationalist. There was also the belief that the ANC wanted lucrative industries, like diamond mines, nationalized and owned by the state. But by the time he became president, Mandela insisted that the African National Congress had been “cleansed” of this sort of ideology—an obvious response to being schooled on White power in the global economy. The ANC’s market economy commitment was given the appearance of a payoff: five months before the ANC came into power, it signed a letter “of intent with the IMF (International Monetary Fund) committing itself as the future government to a program of fiscal austerity in return for an $850 million loan.”

Did the ANC capitulate, did it submit to international realities at the expense of the people who fought, bled and died during the liberation struggle? Or was the ANC faced with a dilemma: Stand up to market forces, and try and create a stimulus program for the people and face the wrath of Whites who controlled the economy and who Mandela felt were needed as allies?

By the end of 1999 barely one percent of South African land had been transferred from White to Black hands. Now approaching 2020 with less than 10 percent of agricultural land in Black hands, South Africa’s land transference program has been described as a dismal failure.

Daniel De Leon, an American journalist describes the Berlin Conference as “an event unique in the history of political science ... Diplomatic in form, it was economic in fact.” It was dubiously dressed up as an humanitarian summit to look at the welfare of locals. Few on the continent or in the African Diaspora were fooled. A week before it closed, the Lagos Observer declared “the world had, perhaps, never witnessed a robbery on so large a scale.” Six years later, another editor of a Lagos newspaper compared the legacy conference to the slave trade saying: “A forcible possession of our land has taken the place of a forcible possession of our person.”

Theodore Holly, the first Black Protestant Episcopal bishop in the U.S., condemned Berlin Conference delegates for having “come together to enact into law, national rapine, robbery and murder,” wrote Gathara for Al Jazeera.

Follow @jehronmuhammad on Twitter.

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!