Europe’s museums and stealing African artifacts

By Jehron Muhammad | Last updated: Aug 21, 2019 - 9:32:53 AMWhat's your opinion on this article?

Michel Leiris

|

–Michel Leiris, letter to his wife, September 19, 1931.

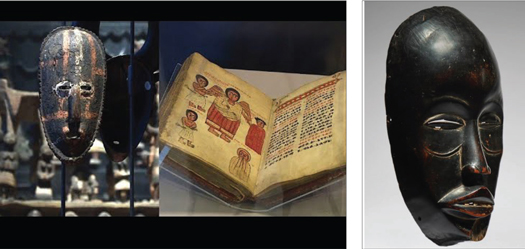

National Public Radio recently featured a story concerning the thievery of African artifacts beginning with an audio clip from the movie “Black Panther”.

In the clip, Michael B. Jordan’s character confronts a White curator over African artifacts in a fictional British museum. “How do you think your ancestors got these?” he asks. “You think they paid a fair price? Or did they take it, like they took everything else?”

In fact, the bigger theft, as described by Chibueze Udeani, in his book “Inculturation as Dialogue: Igbo Culture and the Message of Christ” was Europeans conscious or unconscious uprooting of the uniqueness of what was pronounced in the African cultural world and replacing it with what Europeans considered human, civilized, and valuable.

|

As Dr. Jeanette Greenfield, wrote in her book “The Return of Cultural Treasures,” the Vatican would have you believe it robbed Africa of its cultural artifacts “so that the dawn of faith among the infidel of today can be compared to the dawn of faith which … illuminated pagan Rome.”

In 1925 Pope Pious XI organized an exhibition extolling missionary work from all over the non-Western world. Of the 100,000 items that were taken, less than half were ever returned.

Kwame Opoku writes in Pambazuka.net, “Basically, the churches regarded African sculptures, as part of African culture, as elements of a heathen, pagan culture along with the ‘wild’ dances and music, which accompanied pagan rites. They all had to go and be replaced by ‘Christian’ religion, which meant European culture. In this regard, the churches and the colonialist governments worked for the same final objective: de-africanize Africans and make them amenable to European domination.”

NPR mentions a 2006 exhibition by France’s Quai Branly museum of artifacts being displayed in the country of Benin. These were wooden statues and carved furniture, originally seized from the region by the French military in 1892, and now on loan to the Beninese museum Foundation Zinsou.

The founder of the museum, Marie-Cecile Zinsou, says people lined up for three to four hours, and visitors to the exhibition left lots of messages of gratitude in the visitors book. But the response that got the most attention was why do these artifacts, which were stolen from the area, have to return to France?

The Return of Cultural Treasures

|

The NPR report, “Across Europe, museums rethink what to do with their African art collections,” mentions press coverage that suggests a return of African art “could leave vacant shelves in French museums.”

French historian of Central African art Cecile Fromont says that is not going to happen. She arrogantly justifies holding onto Africa’s cultural heritage because of Europe’s ability to put African art on display. “We are talking about hundreds of thousands of objects,” Fromont says. “As somebody who wants to champion the display and study of the expressive art of the African continent, if we can get more objects on view, in more settings, in more museums, in more places around the world, that sounds like a great solution.”

How did the world’s cultural heritage or artifacts end up in European museums? One source noted the “close attention paid by European museums” during the pillaging of artifacts by European troops strongly suggest they were in cahoots.

“In China (1860), in Korea (1866), in Ethiopia (1868), in the Asante Kingdom (1874), in Cameroon (1884), in the Tanganyika lake region, and the future Belgian Congo (1884), in the current region of Mali (1890), at Dahomey (1892), in the Kingdom of Benin (1897), in present-day Guinea (1898), in Indonesia (1906), in Tanzania (1907), the military raids and so-called punitive expeditions conducted by England, Belgium, Germany, Holland, and France, during the 19th century became occasions for unprecedented pillaging and acquisition of objects of cultural heritage. The type and quantity of the coveted objects, the presence of experts closely attached to certain of the armies, the close attention paid by European museums and libraries, oftentimes far in advance of the movement of the troops, with certain museums already assigned with the housing of specific objects immediately after their acquisition by the armies, shows to what extent the targeted and plundered locations had sometimes much more to do with the museums than military plundering … .”

|

Featured on the NPR program was Senegalese economist Felwine Sarr, who helped author a study on the subject. “The problem is you can’t lend people an object that fundamentally belongs to them,” Sarr notes. The study recommends the return of a wide range of cultural heritage objects taken during the colonial period by force or where there’s simply no documentation of consent.

Recent events in Europe have raised the possibility of repatriations of artifacts to countries of origin, reported NPR. In addition to plans of repatriation announced in Germany, last year French President Emmanuel Macron commissioned a study of how much African art French museums are holding and to make recommendations about what to do with it.

Still don’t get your hopes up. As Alexander Herman of the Institute of Art and Law in the United Kingdom said in 2002, representing a group of directors from major international museums, argued, “We shouldn’t just be kowtowing to these claimant countries and giving everything back, and things need to be shared with a world audience, and we’re the best places where this can happen.”

In other words, what does plundering and pillaging Africa of its cultural heritage have to do with it?

Maybe the next installment of the “Night At The Museum” series featuring Ben Stiller should focus, not on historical characters coming alive, but on cultural artifacts coming alive and returning to their places of origin.

Follow @jehronmuhammad on Twitter.

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!