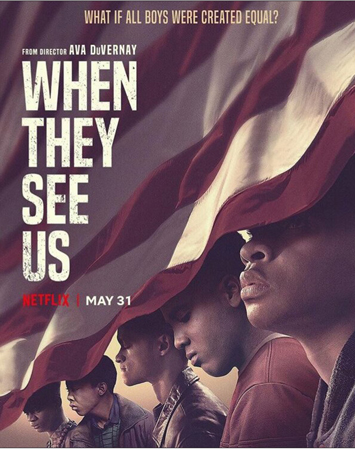

'When They See US' A Stunning, But Often Difficult Series For Black Folk To Watch

By Michael Z. Muhammad -Contributing Writer- | Last updated: Jun 19, 2019 - 8:25:22 AMWhat's your opinion on this article?

|

The boys ranged in age from 14-16 when labeled the “Central Park 5” and convicted for the rape of a White woman in New York’s Central Park in 1989. They were hung out to dry by the media who labeled them a “wolf pack” that was “wilding” in the park, harassing good White people who were riding bikes and jogging.

The miniseries streaming on Netflix in four gut-wrenching parts has received rave reviews from critics, the media and the public. The story is particularly relevant to the Black experience on multiple levels as it deals with unapologetic police brutality, White opinion (called public opinion), the criminal justice system, and the abuse, mistreatment, and manipulation of innocent, young Black children. Yet, there is absolutely little new here, in terms of what Black youth often face.

Weaponizing language against Black people is as American as apple pie. White woman raped, media hysteria, police coercion, Black boys wrongfully convicted after being tortured Abu Ghraib style and forced to confess to a crime they did not commit has happened before. Consider Emmett Till, the Scottsboro boys, the Groveland 4 and more recently the Jena 6 as the racial beat goes on.

The modus operandi remains constant, dehumanize Black people in the minds of the White majority. It has been ongoing since 1555 when the enslavement process in America began.

“I think it is important for the Black community to realize the Emmett Till mentality which dates back to the moment we were brought to these shores and is still persistent,” Attorney and Nation of Islam Student Minister Ava Muhammad told The Final Call in a phone interview. “This myth is manufactured by White males that the Black man’s existence centers around his lust for the White female. That he is by nature, a rapist and a brute and White females are the object of his desires and in constant danger because of that.” The myth of the Black rapist led to the 1955 torture and murder of 14-year-old Till in Money, Miss., after Whites killed him, saying the child visiting from Chicago disrespected a White woman.

The title of Ms. DuVernay’s master-piece could very well be a compelling metaphor for Black people and what White America sees when encountering Black people and especially Black men. The country remains a racist, hostile environment that has never attempted fair dealing with her former slaves.

Many Black people have been unable to watch this critical series because of the psychological pain that it evokes.

“While ‘When They See Us’ is Ava’s masterwork and the way she humanized five boys, and their families was such an act of service and love, I can’t at all shame or blame any Black person who simply doesn’t want to watch or can’t handle the emotional intensity and trauma from the show. There’s so much of it that hits so close to home— the fact police can yank up our children in the dead of night, the helplessness we feel when our boys and girls are locked up, the injustice of the prison industrial complex—that asking anyone to live or re-live these experiences on a screen can be too much to ask,” observed a potential viewer in a Newsone.com article.

Writing for CNN, Doug Criss confessed, “I tried to watch ‘When They See Us.’ I couldn’t even get past the trailer. As scenes from director Ava DuVernay’s new Netflix miniseries about the Central Park Five flashed across my screen, I felt sick. Maybe it was the all-too-familiar images of young black men in police custody and on trial. Perhaps it was the parade of weeping mothers and anguished fathers.”

Newark, N.J., school teacher Keith Howell told The Final Call all of his students have been talking about the drama. “I just can’t bring myself to watch it,” he said. “I’ve reached a period of my life where I do my best to avoid unnecessarily re-traumatizing experiences. At this stage, I must protect my mental health and spiritual peace, end of story.”

In a far-reaching telephone interview, a famed Black psychologist, Dr. Na’im Akbar, waded in on the subject. “Understand,” he said, “our experience in America has been one of brutal treatment. So much of what happened to us is not present in our active memory because so much was done to either distort it or dismiss it.”

Dr. Akbar went on to explain that the last thing White society wants to transmit in its narrative is culpability and Blacks are affected by that.

“It creates an aversion, and we don’t even know why we are averse to it. One of the ways it gets manifested is by denial or an aborting kind of thing. We don’t want to talk about that stuff. We don’t want to see it or re-experience it. It was the same thing with the Roots series. A lot of Black people didn’t watch Roots One or Two.

“By us not having any control, interpreting and understanding the experience, we have dealt with it by repression and avoidance. If you get down to the nuts and bolts, historically Black people are ashamed of their history. As a consequence, you avoid information that would help you to understand better what you went through. ‘I don’t want to know anything about it and put it out of my experience,’ ” Dr. Akbar said.

He concluded that at some point, Blacks need to realize institutions in America were never made to serve them. “They were made to contain us and not enhance us,” he said. “None of them, the justice system, the educational system, the economic system. All of the things that work to help other people navigate this system were made to their advantage and our disadvantage.”

Newly elected Philadelphia Sheriff Rochelle Bilal, a former police officer, heads the Guardian Civic League, the Philadelphia chapter of the National Association of Black Police Officers. She told The Final Call: “From the perspective of a Black police officer, I found the story to be disheartening. It’s not anything that we didn’t know went on in law enforcement. Our job as good officers is to stop that behavior when they see it. If they don’t stop it, then they become a part of it. You can’t claim to be a part of law enforcement personnel and in any way, shape or form and condone this misconduct.”

Ms. Bilal called the story a hard pill to swallow. “I’m glad they made the movie. For years Black police organizations have been speaking out against this type of behavior. It’s time for action. If things are to improve as law enforcement officers, we must speak out against this type of behavior.”

Those responsible for the gross miscarriage of justice portrayed in the series went on to live a good life. Linda Fairstein, the Jewish District Attorney who headed the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office Sex Crimes Unit, and award-winning author in an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal, complained Ms. DuVernay’s dramatization of the Central Park Five case was “full of distortions and falsehoods.” Ms. Fairstein has denied the teens were coerced into confessing, and stood by her belief they were not “completely exonerated” of all crimes, despite a confession from a convicted rapist and murderer and DNA evidence tying him to the jogger’s nearly fatal assault. She has lauded the police investigation as “brilliant.”

She resigned from several boards and the crime novelist and children’s author was dropped by her publisher following social media outrage about her role in the Central Park 5 case.

Assistant District Attorney Elizabeth Lederer, who led the prosecution, still works for the District Attorney’s office. She taught at the Columbia School of Law, until protests forced her to resign June 12. Eric Reynolds, who was assigned to the Central Park Precinct, is now retired. He maintains the confessions were not coerced and the boys were participants in the rape. Detective Michael Sheehan retired from the NYPD in 1993 and went on to become a reporter for New York’s WNYW. He too maintains the five boys were involved. Mr. Sheehan died June 7 from cancer.

Atty. Muhammad said the inability of those who were involved in such egregious injustice reflects the nature of Caucasian people and belief in White superiority and Black inferiority. “Even when the results of a certain set of circumstance go in our favor many cannot handle that,” she said.

“The story should serve as a reminder about how the criminal justice system works. It is not broken,” said Damon Jones CEO of Blacks in Law Enforcement of America. “What we need are people in the system that have a conscience. The other question raised for me is how many more Black men and women and Latino are victims? There are a lot of Yusef Salaams in New York state correction facilities.”

Student Minister Muhammad agrees with this assessment but takes it a step further. “The problem is there is nothing wrong with the system or the laws. It’s the people, the White male mentality and hatred of the Black man. Look at this case in particular with so many flaws. You have to read a person their rights. The law prohibits you from questioning a minor without their parents present and the whole case about their confessions. You have evidentiary laws governing reasonable doubts.”

“A confession by itself is not sufficient for a conviction. The children’s confession is what you call from the ‘fruit of the poisonous tree’ in criminal law, where the evidence you have has been poisoned by how you have obtained it. So the confessions were no good. What is missing is the balance of racial equality, and that is not going to happen in White America. That why we are preaching separation,” she concluded.

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!