Nine Black men endure hunger pains to heal community’s wounds

By J.S. Adams, Contributing Writer | Last updated: May 1, 2019 - 2:52:34 PMWhat's your opinion on this article?

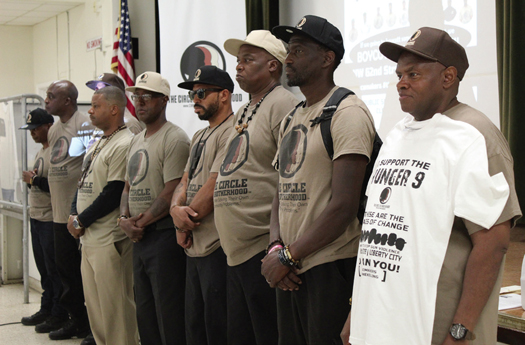

The Hunger 9 stand before community members before embarking on their fast.

|

MIAMI—It all started with pain. Out of that pain came the will to take action to end that pain, and the quick cycle of death.

Nine men in Miami’s legacy Liberty City neighborhood embarked on a mission to catch Liberty City’s—and the world’s—attention.

They didn’t use bullhorns or signs. They didn’t even use their mouths, not for 21 whole days. They withheld the use of their lips and utilized it for their words only, not taking in food for nearly a month, all to speak to the community about gun violence.

Albert Campbell, Anthony Blackman, George Dana Jackson, McArthur Richard Sr., Melvin El, Minister Anthony Eugene Durden, Phillip Muhammad Tavernier, Edward Haynes, and Leroy Jones. ...

They called themselves The Hunger 9.

A hunger strike is born

The Hunger 9 are on a mission to end gun violence, though they are no strangers to crime themselves. Seven of the nine have seen the inside of a jail cell, some for as many as 20 years. But they turned their lives around after their jail time and are now advocates for change.

The Hunger 9 came out of a larger group known as the Circle of Brotherhood (COB). They’re a close-knit group well known in several Miami communities. They work against violence, work to employ former felons and to create a family atmosphere within violence-stricken communities. They’re the ones community members call on when they’re in need.

Now, the COB needed them to listen.

The COB staged Operation Hunger Strike on the corner of NW 62nd Street and 12th Avenue, which holds serious significance. It’s where the 1980 Miami racial uprising started after four Miami-Dade County officers were acquitted of killing a Black man named Arthur McDuffie. It’s also next door to Yaeger Clinic, the first Blackowned clinic in Miami.

Across the street sits Liberty Square, a housing project otherwise known as the “Pork N’ Beans,” which is notorious for its gun violence. It’s also across the street from Sherdavia Jenkins Peace Park, a small playground dedicated to Sherdavia Jenkins, a 9-year-old girl shot and killed in 2006 near her Liberty City home. Gun violence is what led members of the COB to do a candlelight vigil in Liberty City.

“To hear 40 to 50 mothers grieving and wailing in one place ... it was an experience that I will never forget,” said Mr. Campbell, a member of both groups. He was one of the three members of the COB who attended the vigil.

He saw so many women grieving the children and lives lost due to gun violence, but where were the men?

“Our sisters were left to carry a burden that was really too heavy for them. It wasn’t a burden fit for one parent. It was a burden fit for both parents,” he said. “It was because of that experience and the way it moved me deeply, as well as the other three members of the Circle of Brotherhood, that on our way back to our cars we were trying to come up with a plan of what can we do that hasn’t already been done before.”

Releasing of balloons, candlelight vigils, the R.I.P t-shirts ... had all been done before, Mr. Campbell said.

“That gave birth to the Hunger 9 as well as showing our community there are Black men standing up and aiding our sisters,” he said. “We’re holding [Black men] accountable because that is totally unacceptable.”

Mr. Haynes—one of the two members of the Hunger 9 who never went to jail—wants to show that every Black man has a part to play in this fight.

“I am one of the individuals that represents the ‘suite’ side,” he said. “The Circle of Brotherhood represents brothers from the streets to the suites. I’m here to show those individuals who have good jobs, have their own business, that just because we may be better off than the regular brothers in the ’hood, we’re still brothers. There’s no sacrifice that they’re making that we shouldn’t be able to make as well.”

This was Mr. Haynes’ first time fasting.

“It has brought my health into a whole new realm. I came in here with elevated blood pressure, 160 over 115, and now I’m down to normal levels. I’ve gone down to as low as 100 over 82. I’m feeling better now than I’ve felt in over 30 years,” he said.

Living quarters for the nine men were set up on the historic lot. For 22 days, they lived there together, slept on cots under two tents, bathed in a makeshift shower and used a porta potty.

During those 22 days, Mr. Tavernier said none of them lost less than 20 lbs. He lost 24.

“Stopping the gun violence is one thing; stopping the fork and knife violence is another one,” he laughed.

Many members of the Hunger 9 also are entrepreneurs or are employers, including Mr. Tavernier and Mr. Haynes. Mr. Tavernier also holds the 7th Regional Protocol post in Miami’s Muhammad Mosque No. 29.

“I’ve been responsible for employment responsibilities, business responsibilities since I’ve been here and trying to do that while pushing down the cravings, while pushing down the desire for food and those kinds of things,” he said. “The spirit has been very strong. Just to focus on this, on my personal life and those things that still gotta happen, while we’re engaged in this spiritual warfare.”

Support flows in

The men started their fast after a March 10 press conference. They hugged their families because they didn’t know when the strike would end—they were going in without a deadline.

“We did think about 20 days,” said Mr. Tavernier. “Don’t think any of us came in thinking it would take any less.”

Lyle Muhammad speaks to audience members and press.

|

“We want people to see there are Black men here who love and will sacrifice their bodies because they love the community so much,” Lyle Muhammad, COB executive director said during the press conference. “There are people declaring states of emergency for walls ... states of emergency for dog parks. Well, we’re declaring a state of emergency that we need more resources.”

Once the nine started their fast, it didn’t take long for people to start paying attention to what they were trying to do.

On day four, busloads of members from the Miami Rescue Mission stopped by to support the nine. On day six, students from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., stopped by. The school is where 17 students were killed in a mass shooting. On day seven, several organizations poured in at noon, including the NFL Sisters in Service. Several organizations, activists, spiritual leaders and others came to visit. Their story was covered on local television stations and NPR’s Miami affiliate.

But the nine weren’t just idly sitting by. They hosted police sensitivity trainings and community dialogues from their lot.

“I want them to feel the love because our people act the way they act because of a lack of love,” Mr. Campbell said. “People that come from the outside and look at our brothers and our sisters that are doing the shootings that are also victims, too. They look at them as if they woke up like that. A 15-year-old shooter and the one that’s spiraling out of control, he didn’t just wake up like that. He grew up into the person that we see from a lack of love and the major reason is the father is not in the home.”

Nearly each day on the lot, the men focused on some aspect of gun violence. It became a place where people affected by gun violence could bring t-shirts with their loved ones’ faces on it and hang them.

Now what?

On Day 21, the Hunger 9 held a huge press conference and community event to announce their exit strategy. City mayors, commissioners, spiritual leaders, and community members were present.

“Not to disrespect any dignitaries out there—but these are the only dignitaries here today,” announced Lyle Muhammad, pointing to the nine men sitting in the front row. His words were followed by cheers and applause.

Miami Mayor Francis Suarez said, “People like the Circle of Brotherhood have taken ownership over their community.This year, we’re 40 percent below last year’s 51-year low” Miami homicide rate.

Nation of Islam Seventh Region Student Minister Patrick Muhammad speaks at Hunger 9’s press conference and community event.

|

State Rep. Kionne McGhee pledged funds to go towards the Hunger 9’s efforts and pledged to confer with his colleagues to get more funding.

Last to speak were students from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, saying they were excited to work with the Hunger 9 to continue the effort into the future.

“The Hunger 9 is eventually going to pass the torch to you,” Lyle Muhammad told the young people. “Our efforts will continue to move forward.”

The Hunger 9 plans to work with anti-gun violence groups even further south of Miami in an area called Homestead and Goulds, where gun violence has run rampant.

“I realize it’s gonna take that much more in order to just get our people to pay attention. Just to get them to pay attention, it takes 20 days,” Mr. Tavernier laughed. “Just to get some folks who live around the corner who’ve been watching to want to come and take consideration.”

The Hunger 9 are far from done.

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!