Journalists: U.S. media censorship is ‘rampant’

By IPS/GIN | Last updated: Jul 17, 2003 - 9:03:00 PMWhat's your opinion on this article?

- Iraq & the Media (FAIR, Fairness & Accuracy in Reporting)

|

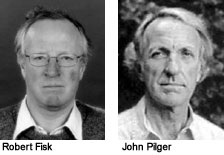

The level of self-censorship in the media has risen, not just since the Iraq war, but also since 9/11, agreed Robert Fisk of The Independent newspaper in Britain and John Pilger, an Australian broadcaster and film-maker.

Both men spoke to IPS on visits to Oslo. Mr. Pilger came to receive the $100,000 Sophie Prize for 30 years of work to expose deception in the media. Mr. Fisk came to give a lecture at Fritt Ord, a Norwegian media foundation.

"Propaganda is not found just in totalitarian states," Mr. Pilger says. "There, at least they know they are being lied to. We tend to assume it is the truth. In the U.S., censorship is rampant."

Self-censorship, that is. This kind of self-censorship is an increasing problem, and leads to one-dimensional coverage that journalists must learn to transcend, Mr. Pilger says.

"The most important soldiers in the Iraq war were not the troops, but the journalists and the broadcasters," he says. "Lies were transformed into themes for public debate. The true reason was of course—as we all now know—not to rid Iraq of Saddam Hussein and remove their alleged weapons of mass destruction, but to achieve the real Anglo-American aim: to capture an oil-rich country and to control the Middle East."

Self-censorship is a particular problem because of the "myth of neutrality" that surrounds Western media. "When you declare yourself neutral, everybody else seems biased," Mr. Pilger says. "But, as seen in the Iraq coverage and elsewhere, journalists very often assume the culture of the media institution and all its unwritten restrictions."

But even the term "self-censorship" is not quite right, Mr. Pilger says, "because many journalists are unaware that they are censoring themselves."

Media organizations are now under tight control, Mr. Pilger says. Just five corporations rule the broadcasters in the United States. In Australia, right-wing tycoon Rupert Murdoch controls 70 percent of the media.

"We live in an age of information," he says. "Yet, the media is not attacking the ruling system. The media has never before been so controlled, and propaganda is all around. Most of us don’t even see it."

The three main dangers facing the world, Mr. Pilger says, are silence, betrayal and power—and journalists can make silence dangerous.

Mr. Fisk says the story in Iraq most correspondents chose not to report was the "bomb now, die later" policy through use of depleted uranium (DU). Since the Gulf War of 1991, the number of cancer patients in Iraq has risen, and "strange vegetables" have begun to appear on the market. The distortions were most likely caused by use of DU, he says.

"I told my colleagues that this was an interesting story that should be reported," Mr. Fisk says. "But most of them said, honestly Bob, we do not want to write home about sick children. An official American military document states that DU dust can indeed be spread in battles and lead to serious illness in humans, but this is not reported."

The public and civil society opposed the Iraq war because they understood the hidden agenda, but "editors have a tendency to underestimate their readership," he says. Readers are seen as ignorant or disinterested.

Self-censorship continues in Iraq after the war, and elsewhere, Mr. Fisk says. "Many more people have died so far in the war against terrorism than on Sept. 11, 2001," he says. "That is the story of our time, and very few are writing it."

Twenty thousand people have died in the still-sputtering Afghanistan war, seven times more than on Sept. 11, Mr. Fisk says. This is just one example of the "great power of silence that is threatening to dominate us all."

Coupled with the self-censorship is the censorship being imposed by the U.S. on the Iraqi media, Mr. Fisk says. This, too, is not being reported adequately in the United States.

The U.S. administration has set up a committee for censorship in Iraq, which means the Iraqi press can publish anything to remind people about the terror of Saddam, but is not allowed to write freely about current events crucial to them and their future.

But Mr. Pilger sees reason for optimism. "There is a movement of resistance globally from the landless peoples movement in Brazil to the huge anti-war movement," he says. "Nothing like this has ever happened before in my lifetime."

The superpower in Washington is being challenged by the other superpower, he says, the superpower of public opinion.

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!