Troubling technology: Video visits costing families of inmates

By Eric Easter -Urban News Service- | Last updated: Feb 8, 2017 - 5:49:34 PMWhat's your opinion on this article?

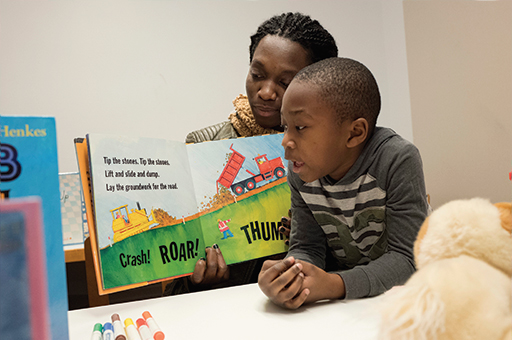

In this Dec. 12, 2016 photo, Justis James, 6, reads a book with his mother, Sherelle Benjamin, at the Brooklyn Public Library as they participate in a Skype video call to her brother, Sebastian Benjamin, at Riker’s Island in New York. The Brooklyn Public Library started the video visitations in 2014 as an outgrowth of the work the library system did onsite at Rikers encouraging detained parents to read to their children, said Nick Higgins, director of outreach services. The video calls are free to the users, and are meant to supplement physical visits to Rikers and not replace them, he said. Photo: AP/Wide World Photos

|

You may have seen the commercials during Sunday football games. A little girl doing her homework and being coached through it by a man via video—her dad. It seems like a normal sweet commercial about a father who can’t be home to help. Except when you look closer, daddy is in an orange jumpsuit, incarcerated.

The advertisement, from the dominant player in prison communications, Securus, is for one of the most controversial new developments in profit from prisons—video visitation.

Aleks Katsjuras, Prison Policy Initiative (R) Atty. Lee Petro

|

And in nearly every case, those new services have come at a significant cost to inmates and their families.

“Securus, GlobalTel and other firms are moving quietly into a model of ‘one-stop’ prison services, gobbling up smaller companies that provide things such as commissary vending, online learning and email. With consolidation, prisons are finding themselves negotiating multiple contracts, but all with the same companies,” said Steven Matthews, the former chief information officer for the Illinois prison system.

Some advocates, while saluting a general move to more efficient methods of communication, are not happy about some of the new devices. “New technology sounds good but comes with its own problems,” Aleks Katsjuras of Prison Policy Initiative said. “In many places, for example, email kiosks have replaced snail mail, which sounds like progress. But where a stamp used to cost 40 cents, the cost to an inmate to send an email (using a kiosk) is now $1.25.”

Of all the new services, video visitation is rapidly becoming the next frontier.

Prison administrators, like those at CCA, the nation’s largest private prison operator, suggest that that system aids security and saves money, primarily by cutting down on staff needed to facilitate a sometimes overwhelming numbers of visitors. They claim it also limits the possibility of contraband being passed from visitor to inmate.

But there is a financial incentive as well. At an average cost of $1.25 per minute, video calls add another layer of costs to inmates. Many prisons also receive commissions on revenue from those visits, sometimes as much as 60 percent.

There is a bizarre twist to the commission structure, however. Prisons are eligible only if those facilities also ban live visits in favor of the calls. It is an incentive apparently hard to pass up. Of the hundreds of prisons that have adopted video visitation, 75 percent have chosen to ban personal visits.

The profit from those commissions can be high. While some states, such as Ohio, do not accept commissions, in North Carolina, commissions from phone calls and video visits topped $6.8 million in the last public reporting, nearly $100,000 more than the much larger state of Texas.

According to Katsjuras, “Prison officials say the money gained from commissions is used for prisoner services, like online learning and rehabilitation, but our research shows that the bulk of the money is more likely to go to staff salaries and contractor payments.”

While the commercials for Securus give the impression that video visitation is just another version of Skype or FaceTime (Securus has a video visitation app), the reality is that families of the incarcerated are disproportionately among the nation’s poorest, and sufficient home computers and hi-speed wi-fi can be rare luxuries.

Many families of inmates, because they lack resources, are still obliged to spend money to travel to prison facilities—where, because of personal visit bans, they must talk to their loved-ones via screen only. And once there, families and advocates complain that the service can be less than efficient, with dropped audio and delayed video streams cited as frequent problems.

Yet some say the real cost of a video visit cannot be measured in dollars.

Lee Petro, the Washington attorney who represented inmate families before the FCC in the fight against prison phone pricing, said “Every study done on prison visitation shows that even a single visit can have a major impact of limiting recidivism. If your job as a prison is to stop people from coming back, why would you ban one of the most effective ways to put people on a better path, then turn around and use the money to pay for new programs that may or may not work? It defies logic.”

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!