National Museum Of African American History And Culture Dedicated

By Askia Muhammad -Senior Editor- | Last updated: Sep 29, 2016 - 1:07:10 PMWhat's your opinion on this article?

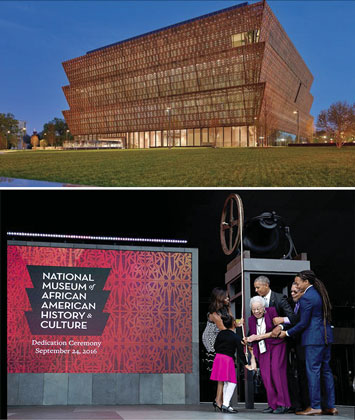

President Barack Obama, First Lady Michelle Obama and the Bonner family ring the Freedom Bell to mark the offi cial opening of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., Sept. 24. The Bonner Family are fourth generation descendants of Elijah B. Odom, a young slave who escaped to freedom. Photo: Twitter/ White House

|

“The great historian John Hope Franklin, who helped to get this museum started, once said, ‘Good history is a good foundation for a better present and future,’” President Obama said in his remarks. “He understood the best history doesn’t just sit behind a glass case; it helps us to understand what’s outside the case. The best history helps us recognize the mistakes that we’ve made and the dark corners of the human spirit that we need to guard against.”

To let some of the local organizers tell it, the building and dedication of the NMAAHC may very well be the most exciting thing that has ever happened during their lifetimes because never before in Washington, has the story of the Black condition in the United States ever been so authoritatively told through African American eyes.

The 150,000 visitors who came to Washington for the dedication made this event far larger than the Annual Legislative Conference of the Congressional Black Caucus, or D.C. Emancipation Day, or the dedication of the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, or the 50th anniversary commemoration of the March on Washington, or the inauguration of the President in the way this museum engaged local residents.

The 75-member D.C. Host Committee organized a week of events held at 25 churches; the embassies of Angola, Haiti, Tanzania, and Venezuela; and at the African American Civil War Memorial in order to welcome the new neighbor. There were poetry readings and concerts; a performance by a 200-member gospel choir, and a vocal and organ music concert by nine Black classical composers.

The museum is literally for many a dream-come-true, and it was 100 years in the making. Black veterans first proposed a national museum of Black American history in 1915, 50 years after the end of the Civil War. Pres. George W. Bush signed the law presented by Congress that authorized its creation in 2003 and its construction began in 2012. Civil Rights pioneer and current U.S. Congressman John Lewis (D-Georgia) co-sponsored the legislation. Its supporters envisioned the museum having a positive affect on local school children.

Young people who go to museums do better in school, according to Frank Smith, Founding Director of the Civil War Memorial. Low-income people tend to go less often to libraries and museums than do middle class people he said, according to a study by the Institute for Library and Museum Studies.

“Our challenge is we have to try to make sure that our young people, regardless of their zip code, regardless of their background, have the same opportunity to visit museums and get just as excited about these museums as others, because this is the way we prepare them for the future,” said Mr. Smith in response to a question from The Final Call.

“This is a national monument,” Mr. Smith continued. “It’s taken us 100 years to build this monument on the mall. African Americans—although our contributions are vast in America—we are actually under-represented in the presentations on the Mall. The reality is there is very little going on down there. We are under-represented in the presentations in the District of Columbia. We’re glad to have this big museum come, because we’re going to bring more people here. It will raise the profile of the various contributions African Americans are making throughout this country and the world.”

Museums can play a major role in education. “Museums in the 21st Century are dynamic learning institutions,” Dr. David Skorton Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution told reporters, “that use the exceptional power of art and artifacts to evoke feelings, teach, and energize people, and at a time of great cynicism and distrust of so many establishments, of the press, and even of government, libraries and museums remain among the most trusted sources of information in our country,” he said.

The museum is rich with documents and artifacts, and tells the story of 500-plus-years of history through the prism of the objects the museum displays.

“This museum is the first time we’re having the opportunity to tell the whole story to the world. Not just to the nation, but to the world,” Dr. John Franklin, a senior manager in the Office of the Deputy Director of the Smithsonian told The Final Call. “People think they know African American history, but it’s more complex.”

Black history is “so essential to the American economy, and the American judicial system, Dr. Franklin continued. “We’re looking at Black incarceration from 19th Century to the present. We have the guard tower from the Angola Prison in Louisiana. We have a cell from there. We’re looking at the role of violence maintaining both slavery and segregation. We have a section called ‘Violence as a means of social control.’”

The museum puts some contemporary discussions, which people generally don’t have into historical context according to Dr. Franklin. “It’s a deep story and involves all of Europe, all of the Americas, all of Africa, and much of the Middle East and Asia. So this will put the African American story in an international context in a way it’s never been done before.”

“The building stands at the crossroads of the past and the future,” said Dr. Skorton. “Virtually all of the objects were donated by people, eager to share parts of their own history with the public.”

For example the Bible, which was owned by preacher Nat Turner, who led a bloody slave rebellion in Southampton, Va., in 1831, is on display; as is the glass-top coffin of 14-year-old Mississippi lynching victim Emmett Till; Rock & Roll musical legend Chuck Berry’s red Cadillac; and a Nation of Islam F.O.I. uniform in the Malcolm X exhibit.

By and large the museum’s Nation of Islam presence is scant—the Malcolm X exhibit is between a display on the 1964 Civil Rights Act and a window depicting North Carolina revolutionary NAACP leader Robert Williams, 1964 author of “Negroes With Guns.” There are also few items from the life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“Opening now, at a time when social and political discord remind us, that racism is not unfortunately a thing of the past, this museum can, and I believe help will, advance the public conversation,” Dr. Skorton told reporters.

“It was in 1863 when Frederick Douglass said, ‘The relation between the White and Colored of this country is the great, paramount, imperative, and all-commanding question for this age and nation to solve,’” Skorton told reporters at the museum press preview. “Over a century and a half later, it is high time to honor the words of this statesman, who began life as a slave. As its mission states, our nation’s newest landmark was created to be a beacon that reminds us what we were, what challenges we still face, and point us toward what we can become.”

“All we knew is that we had a vision,” Dr. Lonnie Bunch, Founding Director of the museum told reporters at the press preview, “a vision that we wanted to get all that encountered the museum to remember: to remember the rich history of the African American. To tell as historian John Hope Franklin said to us: ‘You must tell the unvarnished truth.’ We felt it was crucial to craft a museum that would help America remember and confront, confront it’s tortured racial past.

“But we also thought, while America should ponder the pain of slavery and segregation, it also had to find the joy, the hope, the resiliency, the spirituality that was endemic in this community,” Dr. Bunch continued. “So in essence, the goal was to find that tension between moments of tears and moments of great joy. We also knew that remembering wasn’t enough.

“We needed to craft a museum that would use the history and culture of the African American community as a lens to better understand what it meant to be an American. The goal was to help all realize how profoundly affected we are as Americans by the African American experience. In many ways we discovered that the African American experience is the quintessential American experience. Our notions of optimism, our notions of liberty, our notions of citizenship,” said Dr. Bunch.

“And, yes, a clear-eyed view of history can make us uncomfortable, and shake us out of familiar narratives,” President Obama—who hosted a glamorous reception for museum special guests—said at the dedication. “But it is precisely because of that discomfort that we learn and grow and harness our collective power to make this nation more perfect.

“Yes, African Americans have felt the cold weight of shackles and the stinging lash of the field whip. But we’ve also dared to run north, and sing songs from Harriet Tubman’s hymnal. We’ve buttoned up our Union Blues to join the fight for our freedom. We’ve railed against injustice for decade upon decade—a lifetime of struggle, and progress, and enlightenment that we see etched in Frederick Douglass’s mighty, leonine gaze.

“That’s the American story that this museum tells—one of suffering and delight; one of fear but also of hope; of wandering in the wilderness and then seeing out on the horizon a glimmer of the Promised Land,” Mr. Obama said.

The building depicting that “promised land” is stunning. Its Nigerian architecture is constructed to resemble a Yoruba crown, and the handiwork of blacksmiths in Charleston, S.C. and New Orleans authorities said inspires the actual exterior metalwork.

The building is spacious, 400,000 square feet, housing as many as 37,000 artifacts, with 3,000 of them on display at this time. At least 60 percent of the building’s interior is below ground, where the lowest level displays artifacts from Africa in roughly 1500 before the slave trade began; all the way through to present times with the three levels below ground.

“This is a great moment in the history of this town,” said Mr. Smith.

INSIDE STORIES AND REVIEWS

-

-

About Harriett ... and the Negro Hollywood Road Show

By Rabiah Muhammad, Guest Columnist » Full Story -

Skepticism greets Jay-Z, NFL talk of inspiring change

By Bryan 18X Crawford and Richard B. Muhammad The Final Call Newspaper @TheFinalCall » Full Story -

The painful problem of Black girls and suicide

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Exploitation of Innocence - Report: Perceptions, policies hurting Black girls

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- » Full Story -

Big Ballin: Big ideas fuel a father’s Big Baller Brand and brash business sense

By Bryan Crawford -Contributing Writer- » Full Story

Click Here Stay Connected!

Click Here Stay Connected!